"Get Upstairs, Fuckface, I Can't Keep God Waiting"

Doin' The Caravan Shake with Rawhead Rex, the only folk horror film that matters

Imagine a horizontal line, scratched onto a rolled out piece of parchment in thick black ink. Then imagine that underneath that line the words “Folk Horror Films” have been written in fancy, curly script (you can add an ‘e’ to the end of “folk” if you really must). Now, near the centre of that line, some ghostly roundhead has taken up his quill and etched the names of three movies. They are, as you can probably guess, The Wicker Man, Blood On Satan’s Claw and Witchfinder General. These are the ‘unholy trinity’ of folk horror, due to whom a profitable tea towel industry now thrives. Around those films, dotted across different parts of the line you’ll find the names of others that, to a greater or lesser degree fit into that same loose genre bracket. There’s Penda’s Fen and Midsommar, A Field In England is there, Calibre is all the way over to the left hand side of the line but still in by technical default. Somebody, perhaps looking for a scrap, perhaps in earnest, has added The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Maybe some really clued in motherfucker has jotted down The Borderlands. You get the idea.

Now turn that yellowing piece of papyrus over. See how it catches the light of yon candle? Now look, in the corner, peer hard. What is written there, prey tell? Is it..? Can it be..? Does that say Rawhead Rex?

Yes, Rawhead Rex, the folk horror film that the other kids don’t want to play with. The idiot cousin from the next village over, for whom bourgeois respectability is something to wipe your hairy arse on and who recoils from the A24 logo like a country vicar from a tombola full of severed penises. Not for poor outcast Rawhead the eulogies of Mark Kermode, or a chapter in an expensively lithographed fanzine about walking. No, Rawhead sits alone in a burnt out caravan site, picking the grass from between his toes and the children from between his teeth, and wonders why nobody loves him enough to adapt him as a radio drama.

1986’s Rawhead Rex was among the first attempts to bring the stories of Clive Barker to life via the medium of moving pictures, and it made the author so unhappy that he dedicated himself to directing the next. That next film was to be Hellraiser, and we all know how well that went (there are films that inspire loyalty and then there are films that inspire people to leave VHS tapes on the roofs of bus stops1) but poor Rawhead’s reputation has never recovered. He's too sweaty, too messy, too gory, too… well, crap to be taken seriously.

All of that is hard to argue with. Rawhead Rex is crap. But if you’re bored of what currently passes for folk horror, bored of all the buckles on hats and antlers and creepy things made of twigs and listicles called things like ‘Ten Essential Folk Horror Films’ all of which feature The Witch, which isn’t a fucking folk horror film because it has the ACTUAL CHRISTIAN DEVIL IN IT, then Rawhead Rex is the perfect blast of fetid breath. It is the pinnacle of what happens when you take all the trappings of folk horror - ancient magic challenging the power of Christian hegemony, old stones on blasted heaths, churches built over the sites of pagan ritual - and do a massive shit on them. Indefensible, reprehensible, uncooperative and mean to children, Rawhead Rex is what happens when you cross Nightbeast with Children Of The Stones, and it’s ruddy glorious.

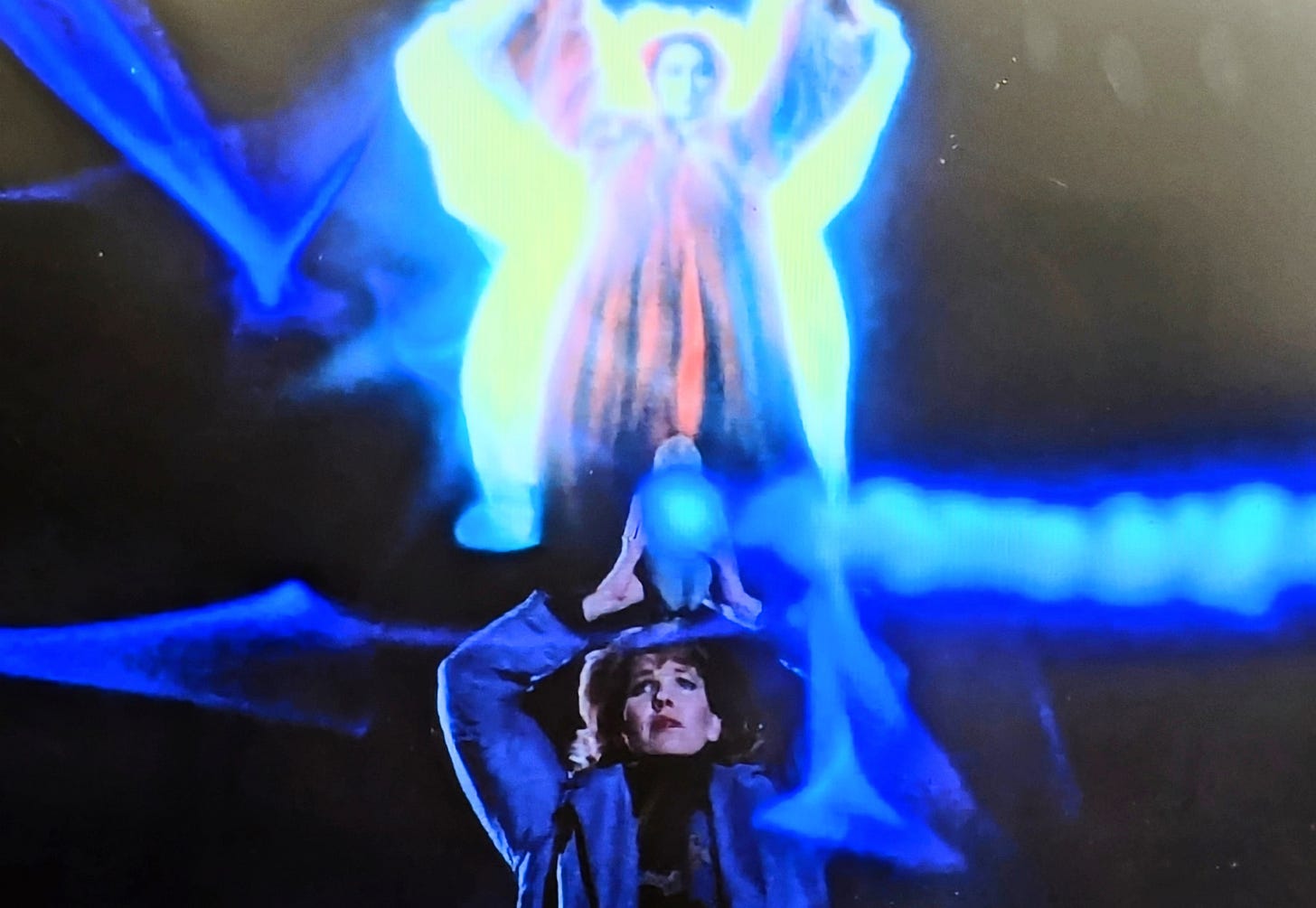

Rawhead Rex was director George Pavlou’s second attempt at adapting a Barker story for the screen, following 1985’s stylish but draggy (and now very difficult to see) Transmutations, both of which had scripts provided by Barker himself, then riding high on the mammoth success of his Books Of Blood collections. An adaptation of the short story of the same name, Rawhead Rex must have seemed a good bet for the movies, being in essence a timeless monster-on-the-rampage story, leavened and spiced with references to ancient pagan magic and with a hefty body count that would fit right in during those post-video nasty days of gleeful carnage. Sadly, while the adaptation is pretty faithful on a beat-for-beat basis, a lot of that atmosphere and flavour got lost in the shuffle, the emphasis on Rawhead’s ancient origins and fear of womanhood being hastily under explained in the last ten minutes, before he’s vanquished by a feminist light show. What the viewer is left with is a monster movie, one that will succeed or fail on the strength of its titular beast.

But what a beast it be.

Introduced springing from the belly of the earth like a brain damaged quarterback jumping out of a birthday cake, Rawhead is one of the 1980’s most singular creations, a studly mixture pitched in the intersection of ‘rural nightclub bouncer’, ‘member of Skinny Puppy’ and ‘fridge from the tip with a Halloween mask stretched over it’. He lumbers gracelessly across the landscape in his tattered leathers and little bootees, emitting proper monster noises like “GRRRRAOW!” and “HUUURRRGH!”, knocking tables over, shaking caravans and being a massive dick to everyone he meets. He is also extremely cross eyed, which you’d think would impair his ability to hypnotise people into doing his dark bidding, but seems not to be a problem. Fair enough. If Rawhead Rex looked deep into my eyes I’d do anything he asked. He’s just that adorable.

But he’s just a monster, and if you know anything about Clive Barker then you know that simple monstrosity isn’t enough. Evil requires a human envoy, someone from this side of the divide to illuminate the depths of mortal depravity. Hellraiser has Julia, a fairytale wicked stepmother updated for the Thatcher era, Nightbreed features Decker, the psychologist and lunatic serial killer, and Rawhead Rex has church verger Declan O’Brien, played by Ronan Wilmot, in what might be up there with Jack Palance’s turn in Hawk The Slayer as one of the most volatile villain performances of the 1980s.

He squints! He screams! He points at things and blasphemes! Wilmot’s performance alone is enough to elevate the film into infamy, whether he’s smashing cameras underfoot, leering out from behind bushes with his big red face, or prostrating himself in front of Rawhead to receive a baptism of steaming monster piss, Wilmot is completely dedicated to eye rolling, cackling villainy, complete with a line in facial expressions suggestive of someone tripping on acid whilst eating a wasp. His scenery chewing and Rawhead’s unfortunate design are two of the pillars upon which the success of the whole film lies.

The third being the film’s sense of location. I’m not sure one could call George Pavlou a great director, but nonetheless the countryside in which Rawhead Rex takes place is, for me at least, extremely familiar. As you may be able to tell from some of the proceeding passages, I have a strong antipathy toward folk horror. Or at least, I don’t like what it has come to represent in the popular imagination. Aside from its reactionary qualities, which is another conversation for a later date, I think ‘folk horror’ and I think of mimsy little silk screened pamphlets with dolmens on the covers, expensive tarot packs on sale in HMV, perfect lanes running between gleaming standing stones, that nice Mark Gatiss, and those posh looking British Library collections of spooky ghost stories. Excessively manicured and stripped of all threat, it’s a vision of the haunted rural that, as someone who grew up in the countryside, does not resonate with me at all.

But Rawhead Rex resonates. Despite its being set in Ireland – County Wicklow to be exact, far away from where I grew up – the village in which it’s filmed is a time capsule to what I remember of rural life circa the year of our lord 1986, with its caravan sites, stuccoed grey post office, sun-warped plastic bus stops and terminally overgrown church graveyards. It’s unvarnished, rough to the touch and borderline hostile in its flat, grey and unshakeable sense of itself. There’s nothing enchanted or enchanting about the location of Rawhead Rex, it’s just been there, unchanged, for long enough to have blended into the landscape. As immoveable and wilfully ignorant as a drunk refusing to leave his bar stool after the ninth pint and as much a part of its natural surroundings as a murmur of starlings or the sound of football boots scraping on hard white cement. It sits, sinister in its ignorance of anything else that has ever been.

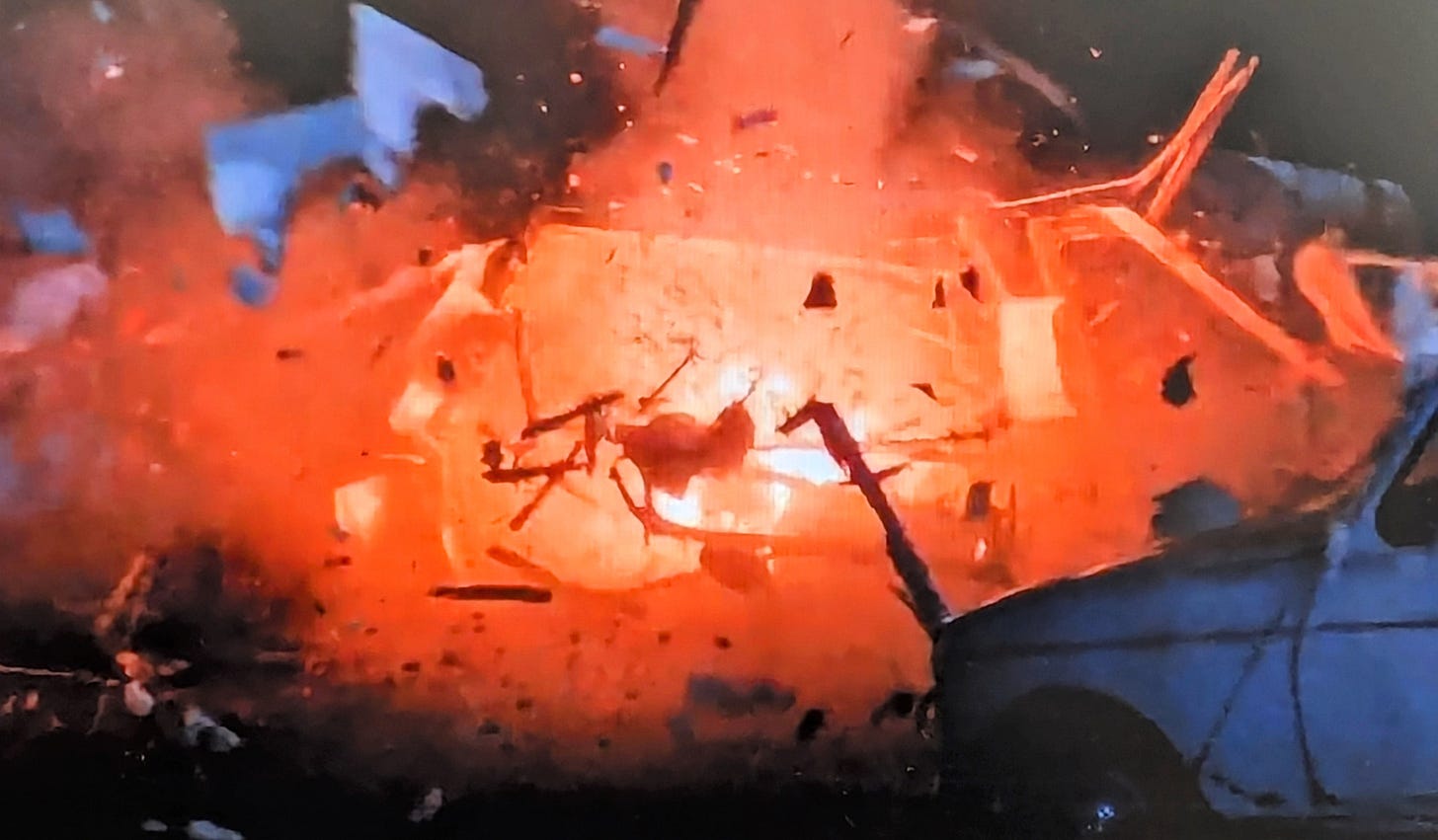

This familiarity extends to the clothes worn by the characters as well. The ice blue jeans and grubby green tracksuits with nonsense slogans on them (‘MUSCLE POWER OK’). The female protagonist’s chunky and angular knitwear, the same kind of stuff my mum and her friends, with their short, feathered hair and dangling gold earrings, would wear on walks on the moors. It’s bracing, being so vividly reminded of your childhood haunts by a film which takes such an unsentimental view of them. With Rawhead burning the church, hanging bodies in the trees, marking his passage with scorched earth and mounds of unspooled guts and representing the gleeful, pagan id of every kid forced to live in a town they were gradually growing too big for.

I’m making that sound like a high bar to entry, like I think that in order to truly enjoy Rawhead Rex you have to have experienced country life in 1986 otherwise you won’t get it. Maybe that’s the case, and some of the more scathing reviews on Letterboxd might bear that interpretation out. But then you remember that this is a movie in which a nine foot reject from Fraggle Rock pisses in a priest’s face and you realise that Rawhead Rex is truly a film for everyone. A blasphemous folk horror for the real folk, that tears through its chosen genre’s veil of respectability with a childish, scatological glee. It’s violent and disgusting and invigorating, and there’s not a single buckled hat to be seen.

https://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/22532/1/londons-hellraiser-vhs-mystery-has-been-solved

Radio 4 - are you listening??!!