Given its focus on horrors beyond human comprehension, and the difficulty of rendering things beyond comprehension comprehensible, cosmic horror does not make for a neat fit with cinema. As the form’s most famous proselytiser, H.P. Lovecraft imagined it, true cosmic horror occurs through the protagonist’s growing awareness of their insignificance when scaled against the vast and uncaring universe. It is a horror of realisation rather than supernatural intrusion and is thus pretty difficult to capture on camera. As a result, while the aesthetics of cosmic horror are often used as dressing to spice up more traditional monster movies – Alien springs to mind – genuine cosmic horror films, that attempt to capture the terrifying helplessness of living in an unheeding universe, are few and far between.

This state of affairs hasn’t been helped by the battering the term has received in critical circles. As with ‘folk horror’, cosmic horror has been reduced to a series of aesthetic cliches, often anything but ‘cosmic’ in their significance and nearly always taken directly from Lovecraft’s work without thought of how they fit into his themes. There is nothing especially cosmic about tentacles, for example, but they’ve become an easily digestible shorthand that has resulted in the selling of a million Cthulhu Beanie Babies and scads of internet listicles about ‘The Best Cosmic Horror Movies’, all of which feature The Thing (a monster movie with Lovecraftian trappings) and none of which include the film that I’m going to talk about here.

Because Jeremy Saulnier’s Hold The Dark doesn’t feature any tentacles, or any other over-imitated signifiers of Lovecraftiana; it doesn’t take place in a quasi-Victorian setting of haunted university libraries and whispered academic knowledge; there are no forbidden books or ancient spells. What it portrays is the terror of a vast uncaring wilderness, the poverty, spiritual and economic, of the people living near it, and the quiet, desperate depletion of their lives as a result.

Based on William Giraldi’s novel of the same name, and scripted by Saulnier’s regular collaborator Macon Blair, Hold The Dark was released on Netflix in 2018 to resounding bafflement. Its reputation for obstinacy is such that, even given Saulnier’s recent success with the excellent Rebel Ridge earlier this year, Hold The Dark is barely mentioned in critical assessments of its director. It’s an outlier in the filmography of an artist rapidly ascending the ladder. A politely tolerated misfire.

Which is bollocks, because not only is Hold The Dark a superlative piece of contemporary eldritch terror, but it also ties neatly into the themes and obsessions of Saulnier’s previous films, the stripped down revenge thriller Blue Ruin and the punks VS skins stand-off of Green Room.

(But first a warning: I am going to spoil the fuck out of this film, so go and see it if you haven’t already. It’s on Netflix.)

Hold The Dark’s set-up gives us just enough contrivance to get the main players into the frame: Russell Core (Jeffrey Wright), a nature writer, is summoned to Keelut, Alaska by a mother, Medora Slone (Riley Keough) to hunt down the wolves responsible for the abduction of several children from the village, including her son. Meanwhile, unbeknownst to both of them, Medora’s husband Vernon is on his way back to Keelut after being wounded on a tour of duty in Iraq. It might be a clue to the confused reception the film received that the results of this seemingly straight forward thriller plot are anything but what you might expect. The film isn’t interested in guilt or suspicion. Russell Core is a witness, not a crime fighter, and the regular law enforcement in the town are in over their heads to an almost comical degree. There are far bigger forces at work here, and justice is not one of them.

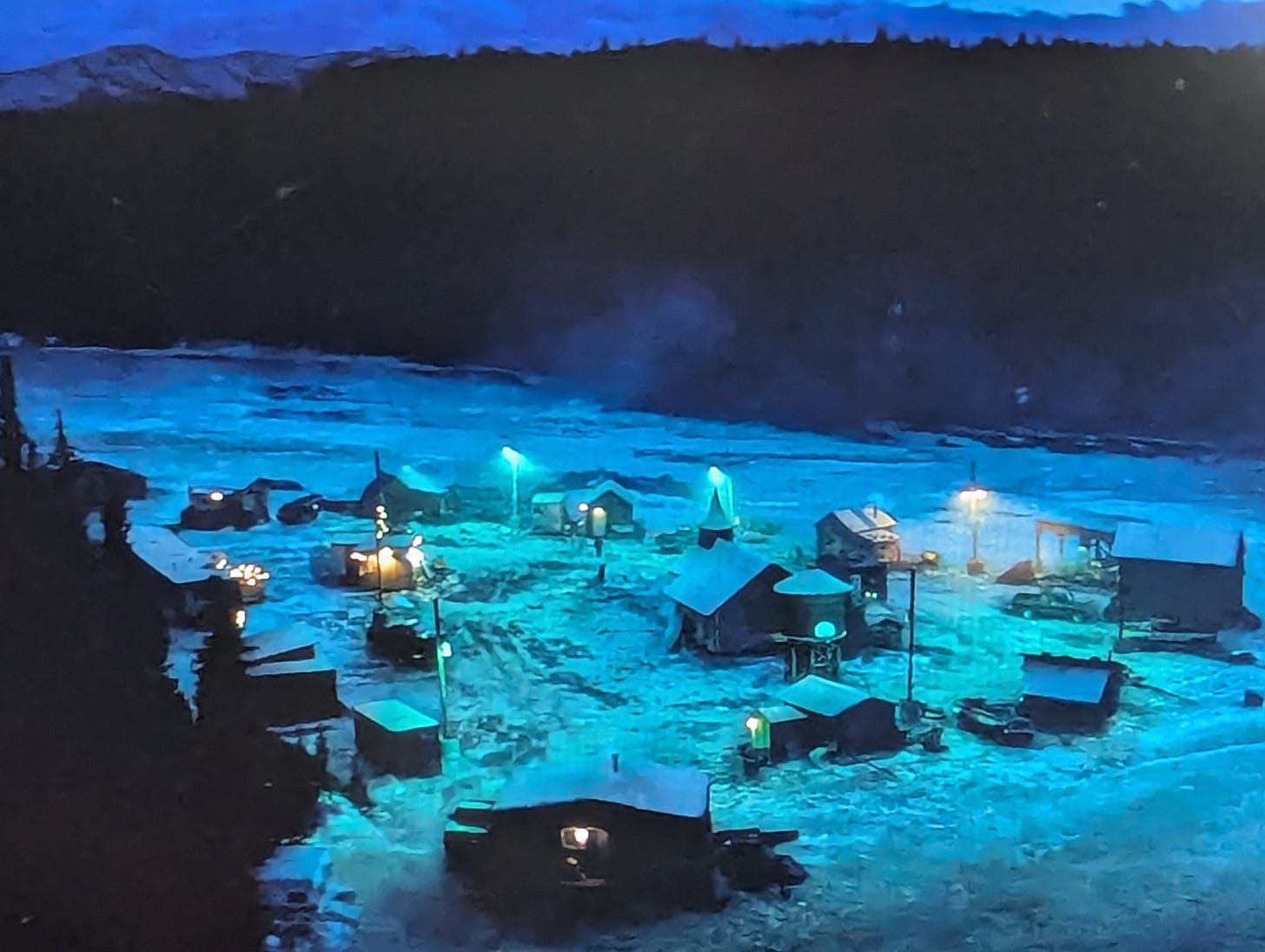

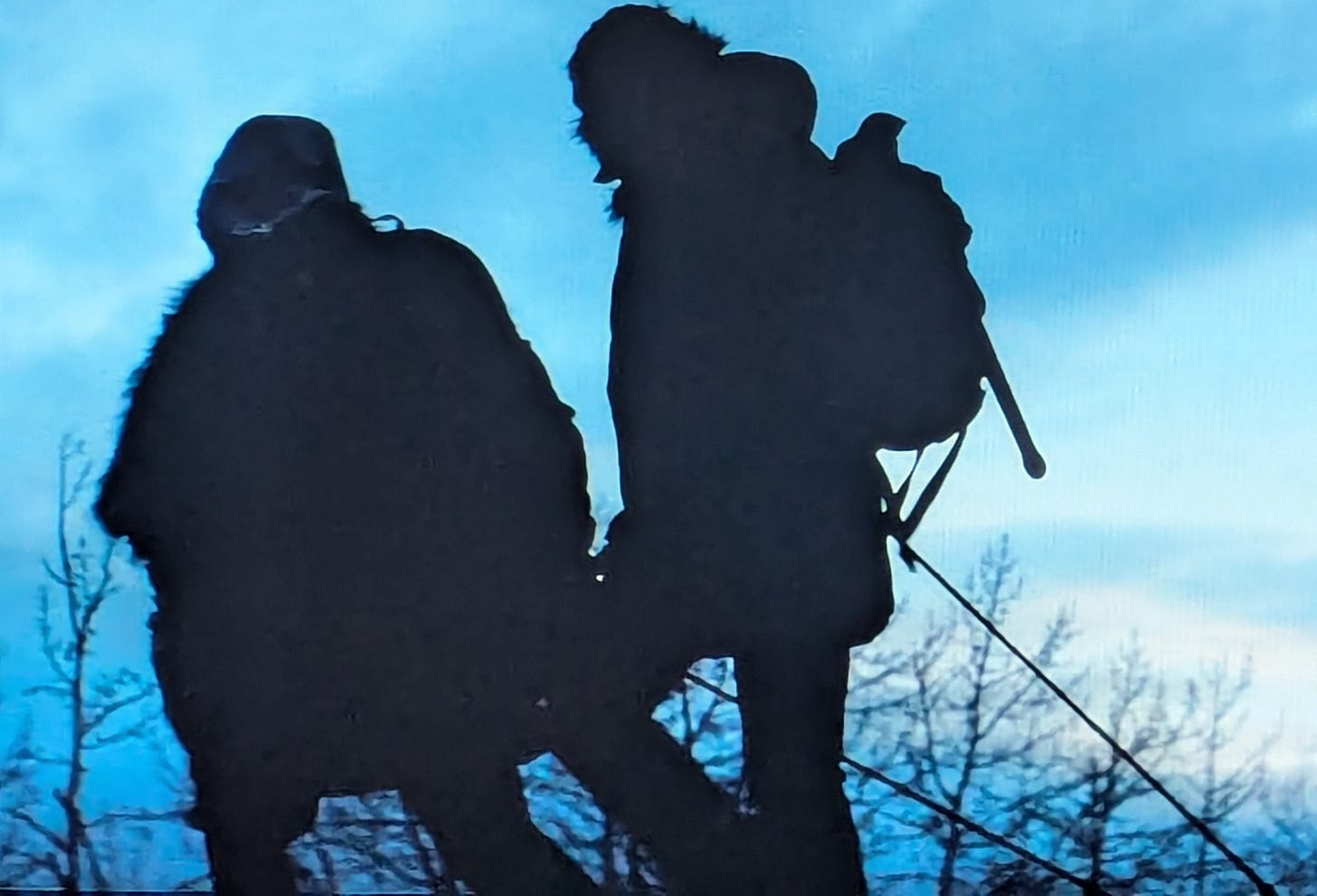

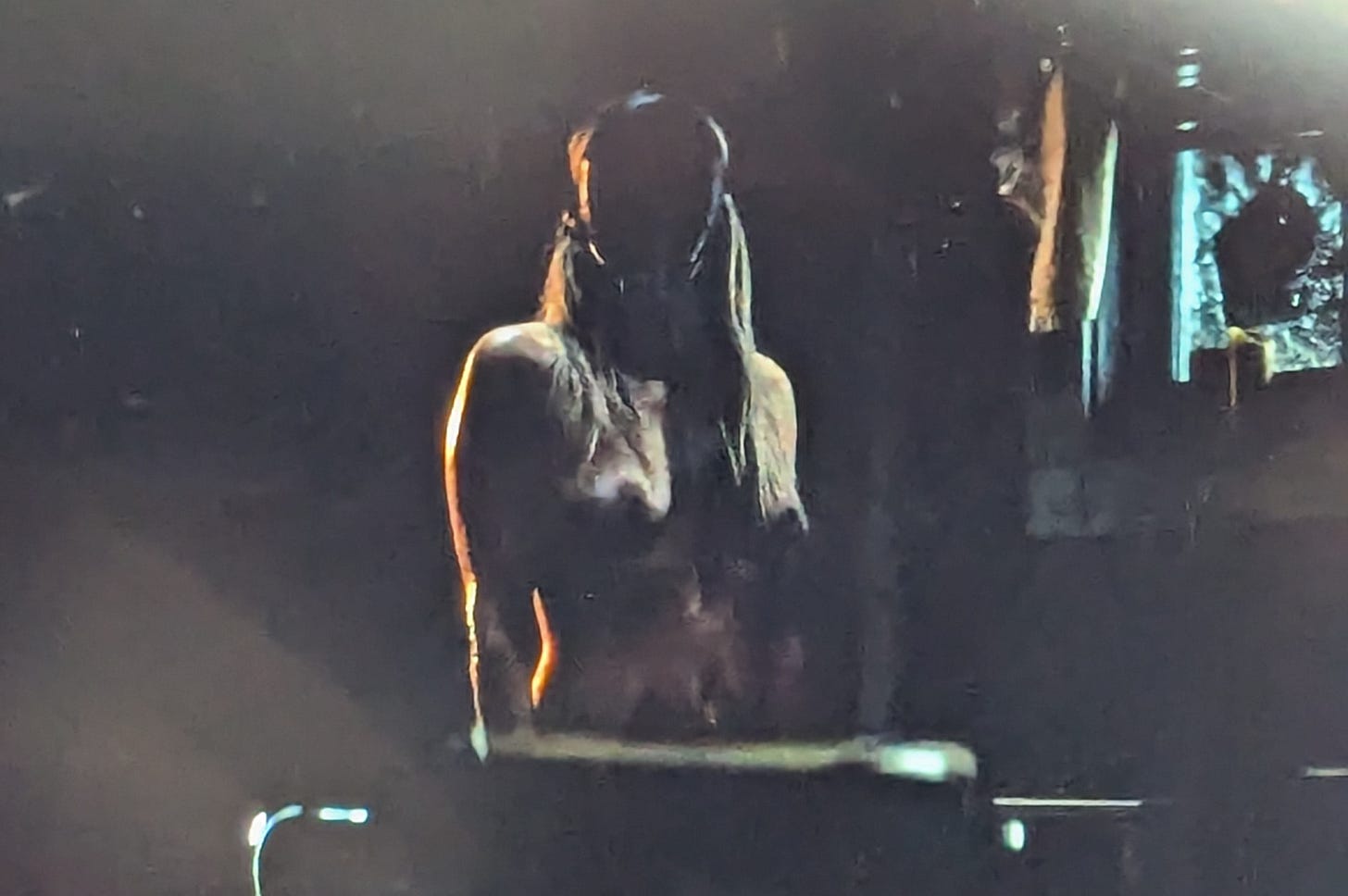

The slow revelations Core experiences over the course of the film paint a picture of part of the world where the reassurances of morality have been crushed to nothingness by the sheer oppressive darkness surrounding its inhabitants. Keelut is the last stop before the wilderness becomes everything, and that wilderness is given palpable force by Saulnier. Townsfolk slump in their shacks as miserable single lamps flicker feebly against the night, and the whole town feels overwhelmed with exhaustion. These are the last people that will ever live here. The dark is winning. When Core discovers Medora’s son, murdered by his own mother, and she takes flight with the body leading Vernon in pursuit, they are not the actions of people interested in anything as simple as guilt or revenge. When Medora and Vernon don their wooden wolf mask, they are enacting steps in a ritual which will bring them closer into the embrace of the darkness around them. Dehumanising themselves to better suit their savage surroundings. Driven by despair, they, along with fellow villager Cheeon (Julian Black Antelope), who demonstrates his allegiance by murdering a squad of cops with a high calibre machine gun in what is probably the best action sequence so far this century, have become death worshippers, living outside of any human restraints or logic. “I’m not convinced the answers exist.” Says the local sheriff, upon learning of Medora’s actions. “They do,” answers Core, “whether or not they fit into our experience is another matter.”

There are clear parallels with classic cosmic horror story telling: In order to welcome their new master, Medora, Vernon and Cheeon have become cultists, worshippers of an aeons-old dark order acting in ways beyond human comprehension. Core is an academic, called upon to witness the manifestations of a strange and terrible ancient power, like any number of Lovecraft’s helpless protagonists. And much like one of his catalogue of unpronounceable deities, the wilderness is a colossal force of infinite indifference, a Nyarlathotep or Azathoth, blindly swatting humans into nothingness. When Medora and Vernon’s final fate is decided – dragging their child’s coffin through the snow as hungry wolves circle - we get a glimpse of exactly what their new God thinks of their hubristic supplication.

Satisfying as these one-to-one comparisons can be, there’s another element to Hold The Dark that deserves remarking on, and that’s its creator’s backgrounds in hardcore punk and extreme metal. Both Saulnier and Macon Blair are avowed lovers of The Heavy Stuff (you can’t make a film as well observed as Green Room unless you know what the fuck you’re talking about) and that love folds back into their work in more interesting ways than the merely cosmetic. As with anyone who’s done some time in the trenches of extreme music, Blair and Saulnier will be aware of the effects of extremist ideologies on some of the more vulnerable members of the scene. How what starts with a Burzum t-shirt can spiral rapidly into identification with antisocial instincts far beyond merely wanting to clatter someone in the pit. In this respect the alienated cultists of Hold The Dark – as with the Nazi punks in Green Room, the revenge maddened protagonist of Blue Ruin, and even the corrupt sheriff’s department in Rebel Ridge - exist as examples of the effects of poisonous anti-human ideologies, and the place that very human neglects can have in shaping them. Hold The Dark is a cosmic horror of the quotidian, far away from any Call Of Cthulhu cosplay, where rather than a sign from an aeons-dead deity, it’s vast and implacable human evils - poverty and racism and alienation - that push normal people to commit unspeakable acts. To hold the dark.

I was glad to see you subscribing to my account, but even more glad to see that your wheelhouse is sordid trash! I don’t write nearly enough about this dank corner of cinema, because i’m always afraid I’ll scare away my highbrow readers. But man alive, there’s gold in them thar hills. With a little encouragement, maybe I could be goaded into those waters once in a while. With some of these artistes— Bava, Argento, Fulci, Corman, etc.— I’m willing to make an unapologetically extravagant case for their artistry.

And Saulnier is intriguing to me because his colleague Macon Blair (Blue Ruin) made an excellent indie film and used a couple of my songs. I’ve seen I think two Saulnier films, both great.

THANK YOU. I thought I'd had a stroke when Rebel Ridge came out and nobody mentioned this. I seem to remember people saying that the story "got away" from Saulnier, but I don't remember feeling that way when I watched it. And that cast is superb.